A Tapestry of Clothes Highlights Border Militarization Cruelty

"Art goes hand in hand with action. Art inspires action, and I think that’s where the role of art becomes effective."

The United States–Mexico border is strewn with abandoned clothes. Migrants seeking legal asylum into the United States pass through gaps in the fence, surrendering to border officials and formally declaring themselves refugees. However, they can only take what fits in an official Department of Homeland Security-issued plastic bag. Everything else is left behind on the ground, as if a group of people simply disappeared.

That curious loss of humanity is the basis for a truly unique piece of art currently hanging at the George Ramirez Performing Arts Academy in Brownsville. “Rivers of Remembrance” is a massive tapestry measuring 12 feet long by 10 feet high. It’s made of clothes, a fast-fashioned pseudo-wall that is both beautiful and grotesque.

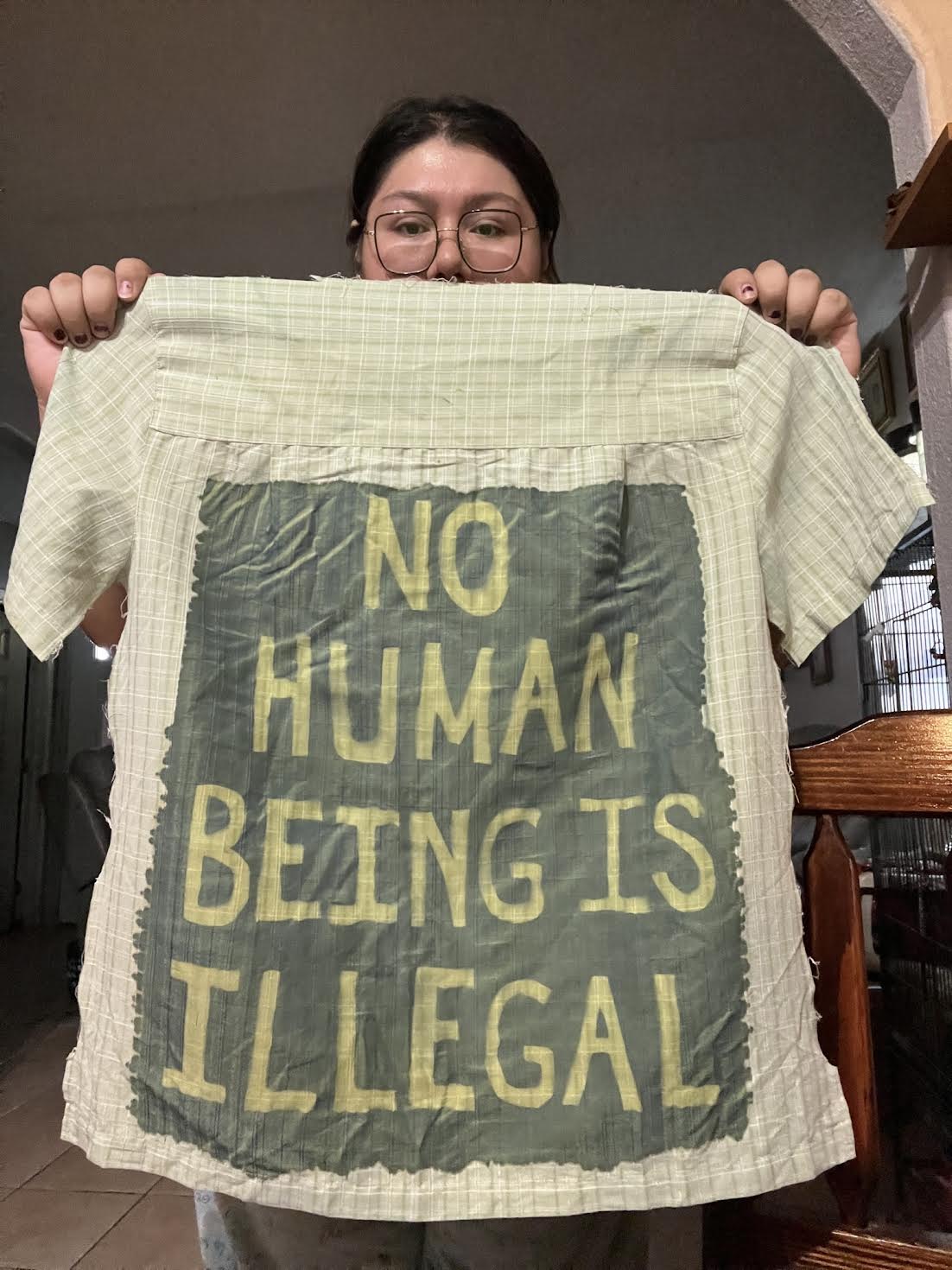

The beauty comes from the vibrant colors, patterns, and messages sewn onto the clothes: “No human is illegal,” in both English and Spanish. The grotesqueness lies in the distortion of the human shape of clothing. It looks like people have been flattened and twisted to form a barrier, an obvious reference to the wall that dominates anti-migrant sentiment in Texas.

The tapestry is the creation of Alicia Garza and Cielo Zuñiga, both members of Voces Unidas, an arts and activist organization in the Rio Grande Valley that promotes healing and civil engagement through creation. Garza, who has specialized in clothing art since college, was moved by the way clothing illustrated the way the border is policed in America.

“The clothing wasn’t the underlying issue, but it was a symptom of the issue,” she says. “People were being dehumanized, stripped of their personal belongings, religious items, everything.”

Zuñiga, who is a self-taught multimedia artist, drew on similar historical art pieces when designing “River of Remembrance.”

“We were inspired by other tapestry and community art projects like the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which uses art as a tool to raise awareness about and memorialize those who lost their life to the AIDS epidemic, and Aerocene, which is an artistic eco-social justice community that is reimagining ways we interact with our planet through air-fueled sculptures,” she says. “We wanted to create a tapestry that represented what one would find along the river, as well as tell a story of hope for the future. We were careful not to understate the realities of the situation while also leaving space for a hopeful future where man-made borders no longer govern where people are allowed to exist—a future where there are only borders like water” and no human being is illegal.”

The piece comes at a time of intense border militarization. Since March 2021, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has stationed Texas National Guard troops at the border under the name Operation Lone Star. Under the guise of border security, Operation Lone Star has strung razor wire across the Rio Grande and committed numerous human rights violations. Abbott’s actions have been praised by President Donald Trump, who instituted mass round ups of suspected migrants as soon as he took office.

The clothes that make up the tapestry are not from the border itself. It’s not really a safe time for two obvious Latina women to be hunting for items around the border. In a way, though, it reinforces the message of the piece. Under racial profiling, many legal American citizens and even Native American tribal members have been rounded up. Having clothes from the American side shows how little difference there is between migrants and the homelanders.

“The clothes from the tapestry are actually not sourced from the border, they’re sourced from our closets,” says Zuñiga. “Which is why in a way I feel even more connected to the piece itself–I get to see my family’s clothes represented in a piece about them and their experiences as immigrants.

The hanging of the tapestry is an important function. At the GRPAA, it’s hung high on a wall, lending it a majesty that it would lack laid out on the ground. It’s similar to the work of Vincent Valdez, whose portraits of people of color are specifically hung higher than his murals of the Ku Klux Klan, diminishing the hate while elevating the dignity.

“There is something about the size of it and the way it covers a wall,” says Garza. “What always stood out to me was how the viewer has to look up. You have to take your time with it. You have to scan through it to catch everything.”

“Rivers of Remembrance” is on display indefinitely at the GRPAA, giving visitors ample chance to ponder its meaning in the wider range of migration politics. Garza appreciates the chance it gives budding artists and their families to engage with the pieces as they are waiting for lessons or performances.

Can it change minds about border militarization? Zuñiga reports that visitors always tell her how it makes them think. They have questions about the clothes and why they are abandoned, and that’s a start.

“I don’t think any form of activism is effective on its own,” she says. “Art goes hand in hand with action. Art inspires action, and I think that’s where the role of art becomes effective. Our tapestry wasn’t a quiet artwork. It was part of a beautiful event inviting the local community to honor and celebrate the life lost at the hands of the border patrol. At the same time, resources were shared, conversations were had, we didn’t let our artwork live one life and then die down. We continued talking about it, showing it, and adding to it. Art becomes an effective form of protest when it inspires further action in yourself as the artist or the viewer. Here we are, almost two years later, still talking about it. That’s a conversation we never would’ve had without art.”

Comments ()