Houston Artist Gets Rightful Showcase At Asia Society

The artist moved to Houston in 1984 and currently lives mere blocks from the Asia Society. However, she has spent most of her long career in obscurity, something "Between Worlds" is keen to rectify.

Hung Hsien, also known as Margaret Chang, is a living bridge between two worlds of art. Nothing showed that better than a tour of Between Worlds, her showcase at Asia Society Texas, which opened last week.

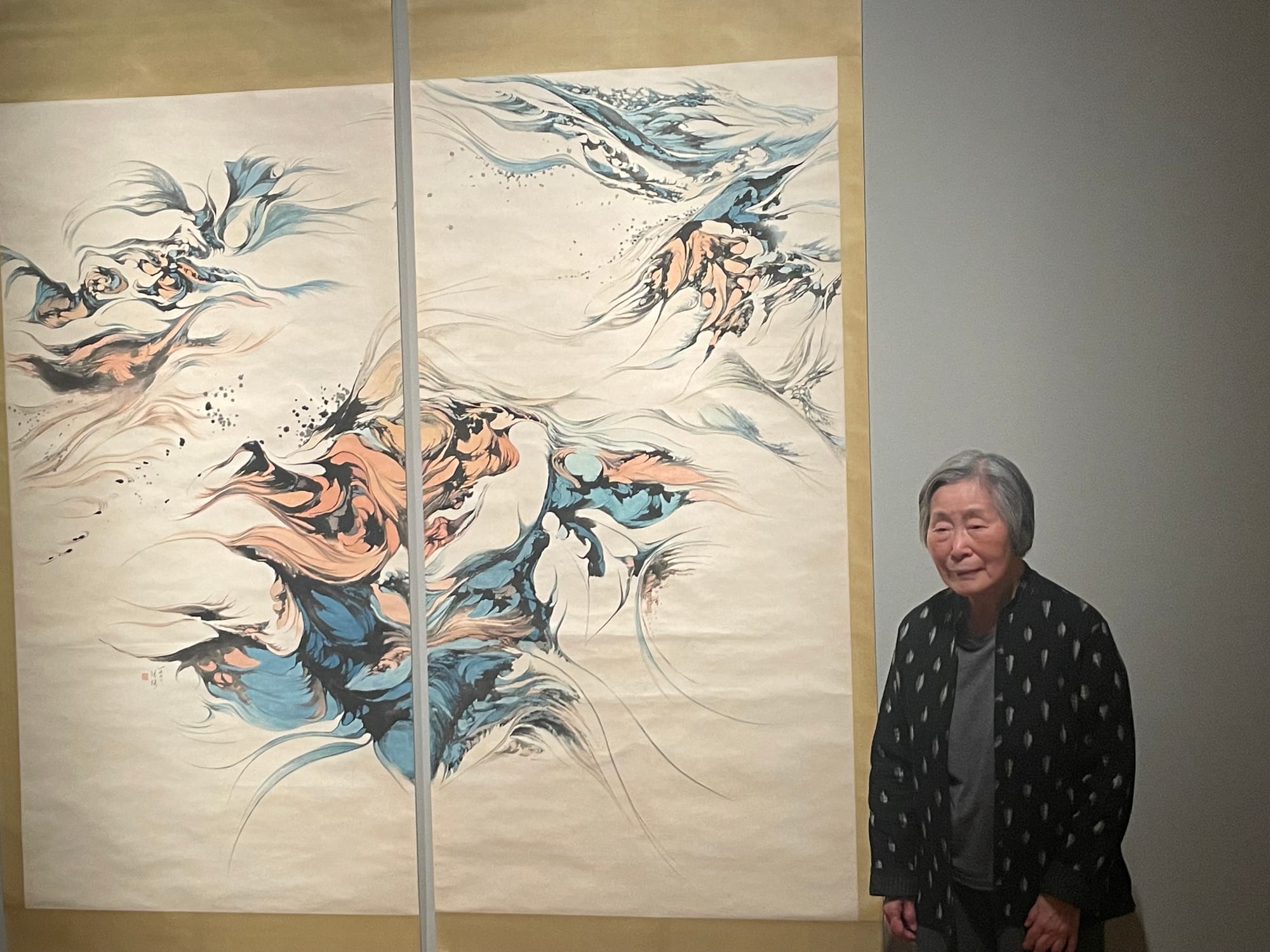

The 91-year-old artist slowly but easily left her wheelchair to pose beside of one of her towering works of art, a diptych of Chinese ink art mixed with Western abstraction, her signature style. Since the 1970s, Hung’s pieces have exuded a sense of quantum energy, as if capturing the idealized atomic existence in rocks, water, and landscapes. Even into her tenth decade on Earth and eighth as an artist, she radiates a transcendental power, smiling effervescently surrounded by her remarkable oeuvre.

The show is curated by contemporary Chinese art historian Tiffany Wai-Ying Beres and Owen Duffy, Asia Society Texas Director of Exhibitions and Curator of the Nancy C. Allen gallery. Hung moved to Houston in 1984 and currently lives mere blocks away. However, she has spent most of her long career in obscurity, something Between Worlds is keen to rectify.

“She’s been this unsung, underrepresented hero of modern Chinese painting,” said Beres in a tour of the show. “When she developed her original style, it was during the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. It was just the beginning of the women’s movement in the United States. And she was a woman. And a minority. And practicing in a medium that really wasn’t well known. She exists in her own space.”

Born in 1933, Hung’s early art education came under the tutelage of Pu Ru, the last prince of the Qing Dynasty who would have possibly been emperor himself if not for the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. Instead, he fled to Taiwan and became a renowned Chinese ink painter, following an artistic tradition that stretches back to the seventh century. Hung would spend hours in his studio, emulating her mentor’s dreamlike monochrome landscapes, which became the foundation of her style.

In 1958, she moved to Evanston, Illinois with her husband, architect Teh-Cheong Chang. For the first time, she studied Western art styles at Northwestern University under George Cohen and Theodore Holkin. One of the pieces on display was her very first assignment, a still life that edges into abstraction because Hung’s English was still poor, and she did not fully understand the assignment. Even filtered through instructions in another language and using an unpreferred subject and style, her genius is clear.

“The tradition in Western art schools is radical freedom,” said Duffy. “It was a major shift for her to go from a rigorous, storied, long-standing system to this space where you could do anything. Her favorite thing about her teachers was that they didn’t tell her what to do.”

Hung enjoyed learning oil painting, surrealism, and other styles, but by the mid-1960s she returned to Chinese ink work, wanting to evolve the form into something for new audiences. This led to her most prolific and impressive period over the next two decades. Chinese ink painting has always been more impressionistic than representational, showing the dreamy ideal of, say, a mountain, than something you could use as a map.

By wedding her Western teachings to that tradition, Hung’s pieces in this period become ethereal, almost alchemical. Rocks in a stream resonate energy out into empty white spaces. A barren wasteland captures the roiling, molten form of primordial creation. As Van Gogh looked up at the night sky and painted the solar winds, so did Hung look at the Earth and ink the kinetic energy in everything.

In 1966 Hung joined the Fifth Moon Group, a community of Chinese artists who revolutionized traditional art forms for international audiences. Hung was the only woman and distinguished herself from her contemporaries as her style evolved into something truly unique. By the 1970s, she had cemented herself into a well-respected artist, even if she still lacked mainstream success.

A stellar work in Between Worlds is a remarkable portrait of planets called “Study for Celestial Globes” created in 1970. Hung’s usual attention to the soul of a landscape is expanded into a trio of planets that emerge from a cosmic fog in swirls of circles. Made during the heyday of the Space Race, it captured the spirit of optimism humanity had for the stars while linking new explorations to the timeless depictions of terrestrial geography made by Chinese masters for over a thousand years. If any work in the entire show represents how Hung has managed to stretch herself between points, this is it.

After Hung moved to Houston, she continued to create. She also developed a love of tai chi, teaching thousands of students in the Houston area, many of whom probably didn’t know that kindly Mrs. Chang was a revolutionary. Hung spent most of her life quietly mastering her craft in her studio, never seeking the limelight. Even now, with a massive retrospective of her work, she remains a humble master of craft.

“She’s never pursued the limelight,” said Beres. “That’s enough for her.”

Between Worlds is on display at Asia Society Texas in Houston daily through September 21.