Houston’s River Oaks Theatre: Ready To Show Again

Houston’s oldest movie theater, the River Oaks, opened its doors again for the first time since 2021 on October 3. Under new direction and local ownership by Culinary Khancepts, it’s poised to become the beating heart of film in the city as it was over most of its 85-year history.

Built in 1939, the River Oaks retains much of its art deco style from the Golden Age of Cinema, back when the healthy neighborhood had a lot more open fields than fancy boutiques. The original balcony was closed in 1989 and was converted to two smaller auditoriums. Aside from that, Culinary Khancepts has done its best to make it look like a brand-new movie palace transported from the past.

I grew up at the River Oaks. That’s not an exaggeration. As a teenager, I performed at the theater’s regular screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show starting in 1995. By 1999, I was a projectionist and manager there, spending something like fifty hours a week on site. Walking into the building nearly brought me to tears.

For the last twenty years of its existence, the River Oaks was a study in contrasts. The looming Greek tableaus of the main auditorium reigned over decaying seats, tattered curtains, and dated projection technology. There was something intensely punk rock about being there, like squatting in a mansion to watch old horror movies.

Previously owned by Landmark, River Oaks was the city’s premiere, sometimes only full-time arthouse theater. While half of the clientele was little old ladies from very expensive houses, the other half was a shifting collection of marginalized people who got to see themselves represented on the big screen. LGBTQ coming of age films, foreign masterpieces, obscure documentaries, and more all got top billing at the River Oaks while the rest of the cinematic world binged on Star Wars, Batman, and The Lord of the Rings.

Program director Rob Saucedo takes that art house identity very seriously. He’s a legend in his own right when it comes to movies in Houston, the mad genius behind Alamo Drafthouse’s dynamite programing and master of strange stunts. One time he had alligators in the theater. Another, the “corpse” of Bigfoot.

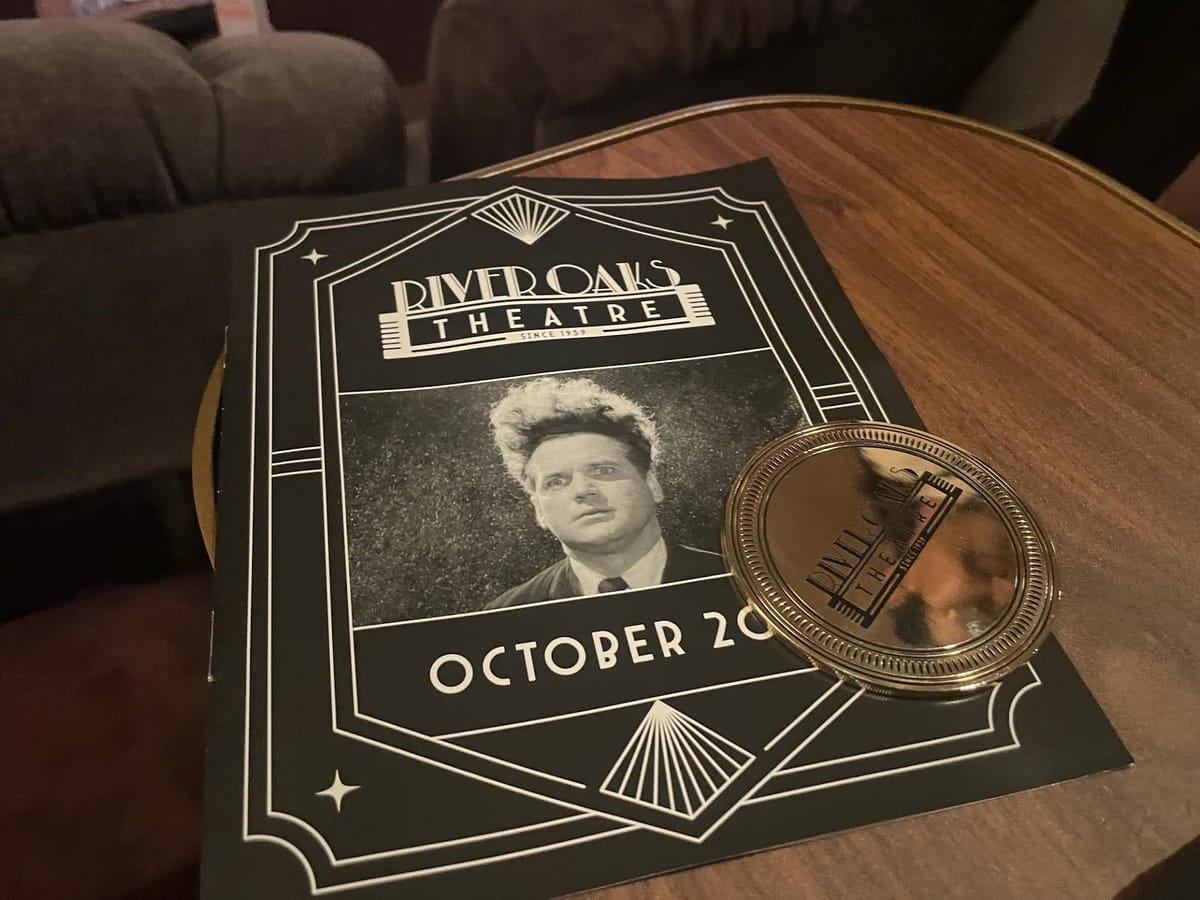

As Saucedo showed media around the refurbished building, he also gave a sneak peek at what the movie schedule would be. The theater has paper programs with schedules and film descriptions, a nice nod to the paper newsletters that Landmark used to hand out at the Rover Oaks and Greenway. Saucedo hopes to expand these into a fill cinephile zine complete with articles.

For now, it’s a manifesto as much as a menu. Jack Nance as Henry Spencer in director David Lynch’s Eraserhead stares menacingly out of the cover. Inside, the most mainstream new release is Joker: Folie à Deux. Technically a blockbuster comic film, sure, but also an artistic deconstruction of mental illness and poverty. It’s a concession to the realism of the business.

“We have do what it takes to make sure this remains viable,” Saucedo said at the press conference.

The rest is what makes River Oaks special. The new animated Latvian film Flow from visionary director Gints Zilbalodis; Alessandra Lacorazza Samudio’s debut semi-autobiographical look at growing up in Colombia, In the Summers; and a release of the previously hard-to-find fantasy film The Fall, starring Lee Pace.

Reading about them in the program and seeing the trailers in a small viewing ceremony brought back every magical, weird movie I’d ever seen at Rover Oaks. In an age when so much is on streaming that it wipes out the mind’s ability to choose, careful curation like this is necessary for discovery. As he did with Alamo, Saucedo is building the community that will see the theater hopefully into the next 85 years.

Nice place for it. The downstairs lobby is tasteful and dark. The popcorn machines and hot dog grills are out of sight, leaving only a first-class bar and employees in white shirts and black vests. It’s a far cry from the dingy candy case and thrift store ties we wore working there in the 1990s.

In the auditorium itself, the old seats have been replaced with plush new ones. Several of these have commemorative plaques people can buy, and two of them are dedicated to director Wes Anderson and Richard Linklater. The capacity is about half of what it was, but it’s infinitely more comfortable.

There is now a full stage, perfect for the concerts, comedy sets, and upcoming revival of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The back room where performers used to have to navigate around rusting machinery is on its way to being a proper green room.

Upstairs, there is another swank bar, a private screening room that feels like a limousine if it was also a movie theater, and the two upstairs auditoriums. I amused some of the staff by telling them stories of the old lift that was used for handicap access before River Oaks installed this new, modern elevator. Often, I literally had to sit on the visitor’s lap to take them up the key-operated chamber.

Jason Ostrow was behind the physical revitalization of the building. Improving disability access was a top priority, though it’s still far below what you’d see in a new theater. Adding more would involve tearing out whole walls, but there has at least been some improvement.

I asked him about the sign out front, the famous marquee. Fixing it was always a non-starter before because of the complexity and age of the original fixtures. According to Ostrow, the entire thing had to be to rebuilt, including transformers from the lights being moved inside where previously they were exposed to the elements.

“Working on it was crazy,” he said. “You couldn’t have ladders out there because the only place to lean them was on the actual neon. To work on the sign at all you have to climb through a window in the projection booth.”

His exasperation made me smile. I used to climb out that window to watch fireworks from the roof on New Year’s Eve. It’s one of the endless architectural quirks of the River Oaks, like the old toilet that sits in that same booth.

The River Oaks is in good hands now. More than that, it’s in caring hands that see how it can mean as much going forward as it did in the past. Being there felt like going home, rather than to the abandoned house I used to live in. It was worth the wait.

Comments ()