New Exhibition Tackles Complicated Emotions Of Pollution And People

Thirty years ago this month, the San Jacinto River caught fire. Storms thrown off Hurricane Rosa in Mexico resulted in heavy rains in Houston, flooding the city and rupturing a 40-inch gasoline pipeline. Fuel poured into the river and quickly caught flame. Waves of fire flowed down the water, destroying homes and buildings on the banks while shrouding the river in a Mordorian darkness under the chemical smoke.

Ashley DeHoyos Sauder, the curator of River on Fire: Artist Activism in the Wake of Environmental Disasters at Diverse Works, crosses that river every day on the way to work from Baytown, and she always thinks about the inherent absurdity of a burning waterway. “It’s an oxymoron, isn’t it?” she asks. “A river on fire.”

The exhibition, being held in the G Gallery of MATCH, is as idiosyncratic as that oxymoron. It hosts art across multiple mediums, each telling a personal story of how pollution in waterways has affected the creator. The odd combination of sculptures, installation pieces, wall art, films, and even furniture gives the collection an appropriate air of flotsam. Like the polluted rivers themselves, shining bits of humanity stick out like embedded shrapnel.

Lili Chin’s “Cetacean Blue” dominates the front of the exhibition. She uses a re-purposed sail as a movie screen, the bottom of the triangle held down with pieces of weathered concrete. On the screen, footage of whales and dolphins in Cape Cod plays on repeat. The projector is set up in such a way that it is impossible to look at the footage closely enough to recognize the animals without the watcher’s shadow intruding into the shot, a subtle point about mankind’s intrusion into nature.

Chin was visiting the gallery, stopping by to check the installation before heading to the airport. A small woman dressed all in black, she smiles when talking about her beloved Cape Cod, though there is a sadness in her intense gaze.

“Sea temperatures that are rising very rapidly,” she says. “It’s like the fastest rising temperature in history. And it’s affecting all the fisheries. So, you’ll see some dead dolphins at the end [of the film]. And that’s also from one of the largest strandings in history that just happened this summer.”

Chin’s focus on the whales isn’t detached environmental judgement. Like all the artists in Rivers on Fire, she is trying to show the necessary balance between nature and human industry. Her piece is flanked by the photographs of Joe Robles, a self-taught artist out of Pasadena who shoots family scenes in the polluted wastelands of the area. Pictures of birthday parties, pregnancies, and play dates sit alongside shots of fences, chemical plants, and the gaping maw of the Washburn Tunnel. The goal is to show that there are people here, living their lives and loving each other.

Chin sees the same thing in Cape Cod and Galveston. “I mean, oil and gas is really a very important natural resource here,” she says. “In Maine. Lobsters are very important over there. We have to find the balance.”

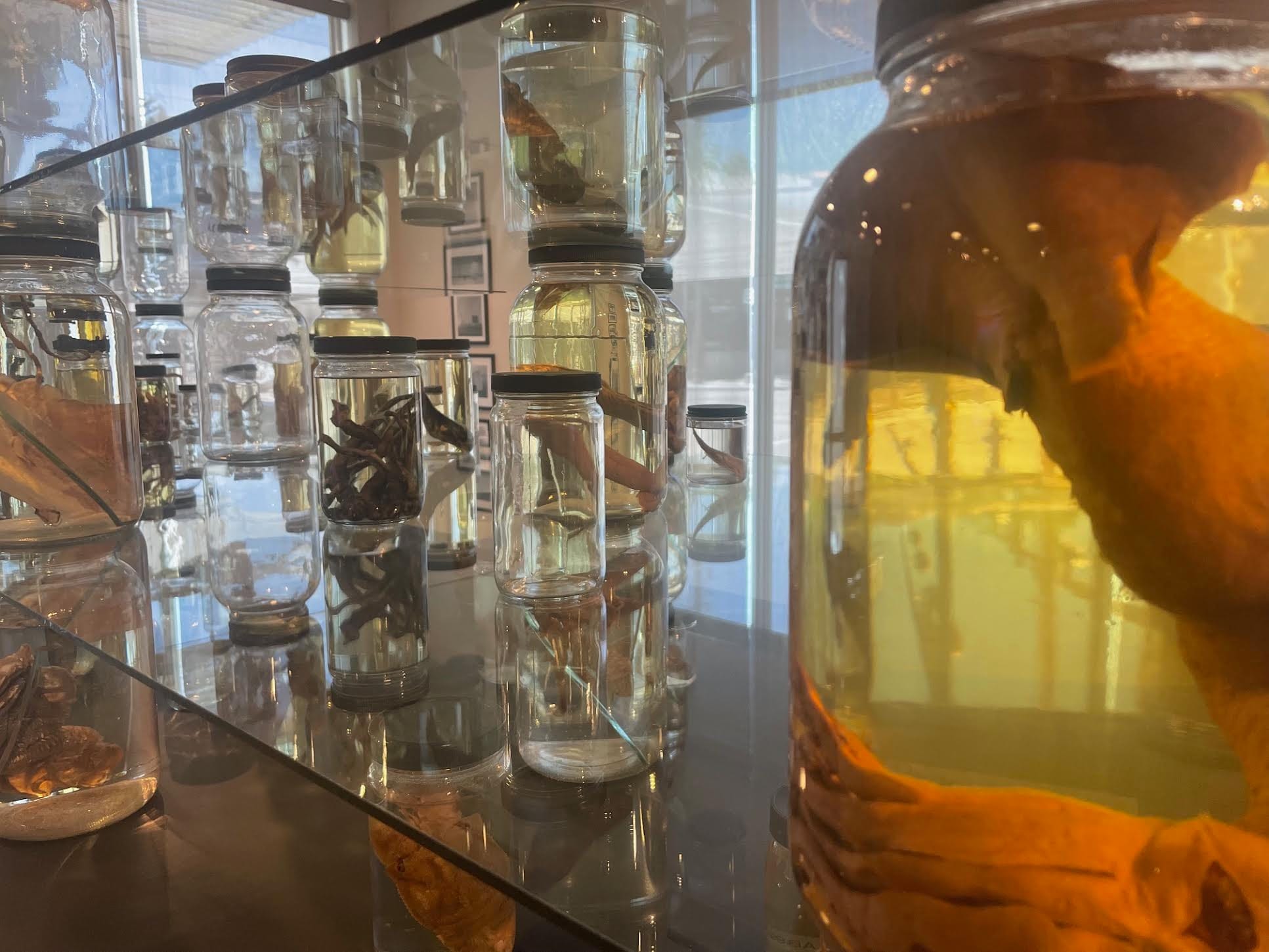

Two other pieces take a more visceral approach. Brandon Ballengee is an artist and marine biologist out of New Orleans. His installation is a collection of preservation jars filled with various marine life from the Gulf of Mexico. Called “Abyss,” the specimens stare out at visitors with a detached lifelessness, reminding humans of the widespread effect our drilling has on hundreds of species. Several jars sit empty to represent the gaps in our knowledge.

Manuel Alejandro Rodriguez-Delgado turns that same medical focus on the human side. His piece is a mounted respirator used to filter pollutants out of the air. Pushing a button turns it on and fills the room with a sinister hissing breath.

Not everything is doom and death. Zuyva Sevilla from Albuquerque, New Mexico is another artist who was visiting to see how his piece was faring. He positively bounces as he talks about his installation, his hair swaying gently back and forth like wildflowers in a breeze.

“Sink 19” is a series of vertical panels mounted on the wall and made of thermal reactive material. Attached to each are heaters and fans, creating spots of visible energy. On the far wall, a thermal camera incorporates the viewer into the piece when they move in front of it.

Much of the pollution in the Houston area comes from our relationship to energy. When the lights went out during the last storms, it often felt like electricity was a capricious god that needed to be appeased to return the air conditioning. Disassociation with the mechanics of energy was one reason Sevilla created his piece.

“We can actually see these movements that are happening kind of just outside of our spectrum,” he says. “Of course there is a lot of baggage with thermal imaging, military usage and border crossings. In this case I am kind of re-appropriating that technology and using it in a very curious and artistic context.”

River on Fire is a diverse collection of experiences related to pollution, as well as a remarkable exhibition of cutting edge and rising artists. It’s impossible to come away from it without at least questioning how we think about the interaction between people and the environment. As climate change continues to affect how we live, such art becomes increasingly necessary.

River on Fire is open through November 16 at MATCH, 3400 Main in Houston. Free admission. Visit DiverseWorks.org for more information.

Comments ()