San Antonio Artist Vincent Valdez Takes Over CAMH

Visiting the new Vincent Valdez career retrospective, Just a Dream, at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston is like admiring a sunrise, only for the sunrise to admire you back. It’s gargantuan, liminal, and positively radioactive in its impact.

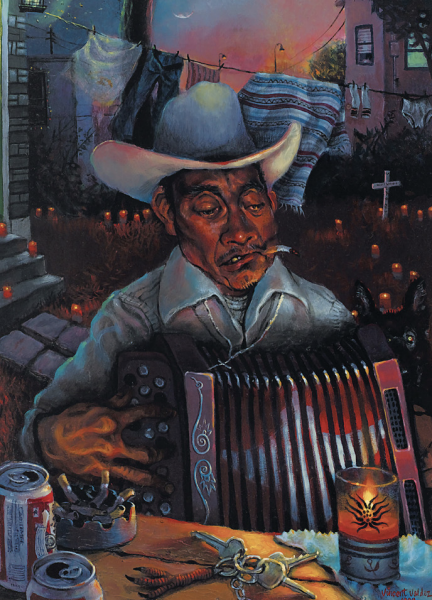

Born in San Antonio in 1977, Valdez has long been one of the nation’s most impressive artists. The current exhibition took five years to coordinate between CAMH and the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), gathering Valdez’s enormous pieces from across the world, including from the renowned collection of Latino art by actor Cheech Marin. Now those pieces fill the CAMH, turning the building into a temple dedicated to the worship of dawn/dusk on the human form.

Michael Robinson, CAMH’s communications and marketing manager, gushes about the liminal aspect of Valdez’s work as he conducts a tour. One remarkable piece is Dream, a large square canvas supported on cinder blocks. It depicts a boxer after a difficult fight, his face puffy with punishment but his eyes bright. It’s impossible to tell whether he won or lost.

Next to him is a series of panels called The Strangest Fruit. These are more masculine figures dressed in everyday clothes, including sports jerseys. Their feet do not touch the ground. Valdez was inspired to create them by the history of lynching against Latino and Black Americans, but there are no ropes, trees, blood, or violence.

“They could be angels rising up,” says Robinson. “That’s the most genius thing about Valdez. You can never tell if his subjects are rising or falling. The viewer has to make their own context.”

Houston DJ Dan Castillo remembers the first time he saw the panels.

“I stumbled upon Valdez’s work while visiting the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio in November 2023,” he says. “The Strangest Fruit stopped me in my tracks. As a gang and race-related violence survivor, the painting motivated me to learn more about the artist’s work. Learning that he is from the south side of San Antonio, and had graduated from the same high school that my mother and many of my relatives attended, I felt an immediate connection, a clear understanding of the artist’s work and point of view.”

Valdez often addresses violence against Americans based on their race or circumstance. Downstairs is a collaboration with his partner Adriana Corral, a statue of the Virgin Mary with cracks to let light through. The piece is dedicated to José Campos Torres, a Mexican-American veteran beaten to death by police the year Valdez was born. It remains one of the worst hate crimes in Houston history.

It’s the favorite piece in the exhibit for Houston artist Lizbeth Ortiz.

“We still see this happening in different forms, sometimes reported, sometimes not,” she says, referring to Torres. “It’s still relevant today. We try to think we’ve learned and come a long way, but have we? [Valdez] gives a glimpse of faith and hope if we keep our past and learn from it.”

Just a Dream is not an atrocity attraction or a parade of torment. Valdez is no cheap gore merchant mortgaging Black and brown pain for freakouts. Instead, he uses the subtlety of composition and light to turn horrible things into potentially hopeful ones.

An entire wall of CAMH holds a mural-sized painting of a KKK rally. The figures are huge, like most Valdez subjects. Even the baby in the little KKK uniform is nearly the size of a teenager. The Klan gazes across the floor at Valdez’s other works.

However, it is hung lower than them. The giant Klansmen are eye level with an average size viewer.

“I can look hatred in the eyes,” says Robinson. “Then I can walk away.”

The same cannot be said for the Valdez’s series of portraits, The New Americans, titanic figures of Latino people in cityscapes. These figures tower over the Klan, looking back and down at them from opposing walls as if recognizing how small their hate truly is. Even a painting of Valdez’s grandparents dressed in day labor gear seems to hover above and beyond the racist glares.

The result is something holy. Valdez’s use of light, particularly the mutable and indistinct light of sunrise and sunset, always gives his subjects a sense of motion and mystery.

“I don’t like using the term ‘the artist of their generation,’ but he definitely is the visual voice of what is America is to us all today,” says Ortiz. “He doesn’t sugarcoat anything. I think it is incredibly humbling to see his mastery of every medium he has tackled and how he has adapted the lighting of the Renaissance. But it’s contemporary. It makes you feel like you’re in church in a way.”

Just a Dream runs through March 23, 2025.

Comments ()