The Mask Makers of Texas

The mask is a cornerstone of Halloween. Some people wear them to frighten others, enhancing the spooky nature of the season. Others use them as a form of trickery or roleplay, paying homage to the idea that Halloween is a time when the veil between worlds thins. Something about the mask reduces the measurable amount of perceptible reality.

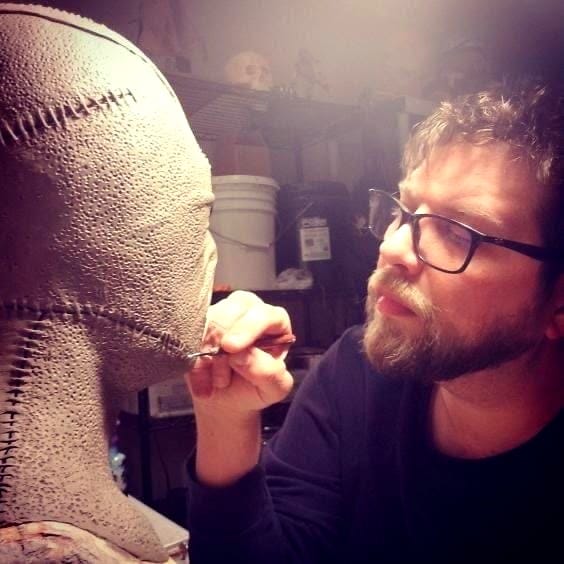

Ryan Pawlak, an effects artist and mask maker in Houston, knows the power of masks well.

“Did you ever see The Mask with Jim Carrey? They talk about how we all wear metaphorical masks,” he says. “When you have access to an actual mask, you know you’re hidden. There’s a comfort to the anonymity. I’ll be wearing a werewolf mask this Halloween, and I know I’ll act ways I wouldn’t normally do when people know it’s me. Masks lower inhibitions.”

Pawlak has been in the mask business for more than a decade. In 2013, he attended the Tom Savini Make-up Effects Program, established by the legendary make-up and effects artist behind The Prowler and Day of the Dead. He went to California to work with Nightmare Forest, making gore effects and other models for film and television. Once, he helped cast the fiberglass head of a Great White Shark for NCIS.

“I felt a little bad about how much we had to charge them to make that, but then I found out they had a budget of $450,000 per episode,” he says. “As long as you have the money fountain turned on, I might as well jump in!”

Things are not as rosy these days. Despite living in a golden age of horror, much of the independent mask market has been decimated by COVID. Though artists like Pawlak still get personal commissions for latex and silicon masks through Instagram, the main way of making money was to make masks to sell at horror conventions. The pandemic ended that industry, leaving most independent professionals with a few referral clients.

Not all, though. Jennifer Harrison has been making masks in the Fort Worth area since 1997. Her work is very different from the gore-driven movie monsters most people think about when Halloween masks are brought up. Instead, she works with leather, crafting masquerade style masks that can still be quite scary, but also aspire to elegance.

She got her start while visiting the Scarborough Renaissance Festival’ back when it was still just called Scarborough Fair. Harrison saw a stand of leather masks and was captivated. Rather than buying one, she went home and learned how to make one.

“There was barely any internet then,” she says. “So, I was off to the library. I made one, then another, then another, and here I am now.”

The work has also given her some perspective into the impact of masks. Harrison is fascinated by the concept of face pareidolia. When you look at your cars and the headlights seem like eyes while the grill forms a mouth, that’s face pareidolia. The human tendency to anthropomorphize alters the mask into something both face and not-face.

“A mask takes the face and hacks it,” she says. “It changes what you perceive about the face. The face doesn’t look right and drops you in the uncanny valley.”

Like Pawlak, she’s watched things change over the years. The mainstreaming of science fiction and fantasy has helped, as is evident by the Cthulhu masks she sells. Lately, a lot of her masks are for concerts and raves. She’s made leather versions of the masks from the band Slipknot and monstrous designs for Lady Gaga events.

“People feel more comfortable in masks now,” she says.

Pawlak has pursued other work too. He was an integral part of the Houston Grand Opera’s production of George Frideric Handel’s Saul. There is a scene where a witch appears and breast-feeds Saul. The actor playing the witch was an old man, and Pawlak had to construct a fake chest with lactating nipples so that Saul could sing with a mouthful of milk.

“I think I used a plastic liquor flask and water bottle nipples,” he says. “Ironically, the actor playing Saul was severely lactose intolerant, so I had to devise something out of water and non-dairy creamer. The whole thing was super complicated, and I spent every performance in the wings in case there was a [breast] emergency.”

Pawlak left the opera shortly after because of scheduling conflicts, though he sometimes returns to teach the next generation or weirdsmiths. The money that comes in from commissions helps, and he remains affiliated with Nightmare Forest as a mold maker, but the mask industry still hasn’t recovered.

“It’s becoming a dying business because so many people are doing it out of their garages on a commission basis,” he says. “I love it, but there’s no stability anymore.”

Harrison vends her masks at various fairs and sales through her website. However, she often just breaks even despite some masks costing over $300. She remains in the industry for the love of the craft and the chance to meet people.

“Someone told me my masks were creepy, sexy, and cool,” she says. “You can’t put a price on that.”

Comments ()