The Texas Chain Saw Massacre At Fifty

It’s 1974, and in Round Rock, Texas, the devil is about to die a gruesome death. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre* released in theaters, and horror has never been the same.

The occult almost completely dominated the horror film scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Just a year prior, The Exorcist and The Wicker Man glued audiences to their seats with tales of demonic possession and pagan human sacrifices. The world was still reeling from the trial of the Manson Family in 1971, a cult that had murdered the wife of Roman Polanski, director of that other Satanic horror staple, Rosemary’s Baby. When the murders first happened, police assumed it had been the work of devil worshippers. That fact that Manson claimed connection to occult groups like the Process Church of the Final Judgment left the public with a vague certainty that atrocity could be safely assigned to the devil and beaten with devout Christianity.

While everyone was congratulating themselves, a young director named Tobe Hooper was getting angry at the long lines in a home improvement store. In his frustration, he spied a chainsaw, and thought it could definitely cut crowds. That errant thought led to his collaboration with Kim Henkel on the script that became The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Despite its tiny budget of $140,000 ($700,000 in 2024 USD), low brow premise, and grindhouse aesthetic, TCM is now widely regarded as one of the greatest horror films of all time. Alongside Black Christmas (which was released the same day), it birthed the slasher sub-genre that would dominate horror for the next two decades.

The film follows a group of young people who travel to rural Texas to investigate reports of grave-robbing where their grandfather is buried. In doing so, they stumble across a family of deranged cannibals, including the hulking Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen), who wears human skin masks. One by one, the intruders are slaughtered, with only Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns), narrowly escaping in the back of a passing pickup truck with Leatherface in close pursuit. With his prey a dwindling speck against the rising Texas sun, Leatherface screams in rage at the sky while dancing maniacally with his saw.

Two things have always made TCM stand out against its brethren. The first is its nightmare-like quality. The film effortlessly dips between absurdism and brutality, such as in the infamous dinner scene where the family tries to help their nearly dead grandfather kill Sally with a mallet. When Sally does initially get away, she is caught and brought back, which will be very familiar to anyone who has had bad dreams of being chased in the dark.

The other was its sheer grittiness. Between the opening screen crawl saying the events of the movie happened (they didn’t), and the gritty film quality (it was shot on an Eclair NPR 16mm camera), TCM resembled a documentary more than a typical Hollywood horror flick.

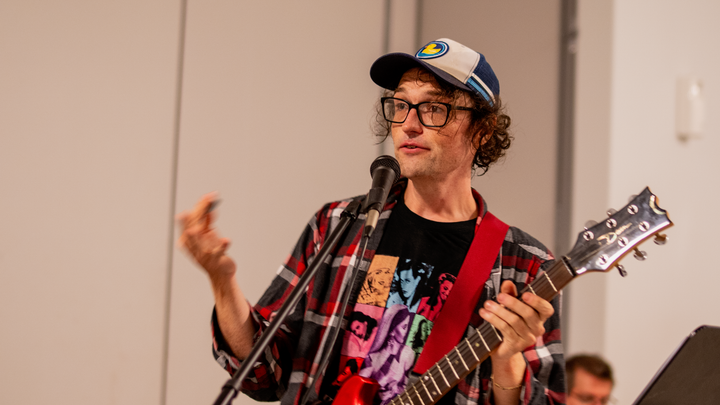

That realism drew Texas filmmaker William R. Instone to TCM. He has, quite literally, lived in the massacre's shadow his whole life. When he lived in Marble Falls, he got to watch the house the movie was filmed in dismantled, moved, and rebuilt in Kingsland in 1998. There is a bridge in Bastrop that features prominently in Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and Instone regularly drives along that bridge.

He was ten years old when he saw TCM, and it made an immediate mark.

“It was one of those films that felt real,” he says. “These looked like real people and it was so scary that it could really happen. You go out to a secluded area, you could die. You think that when you’re a kid.”

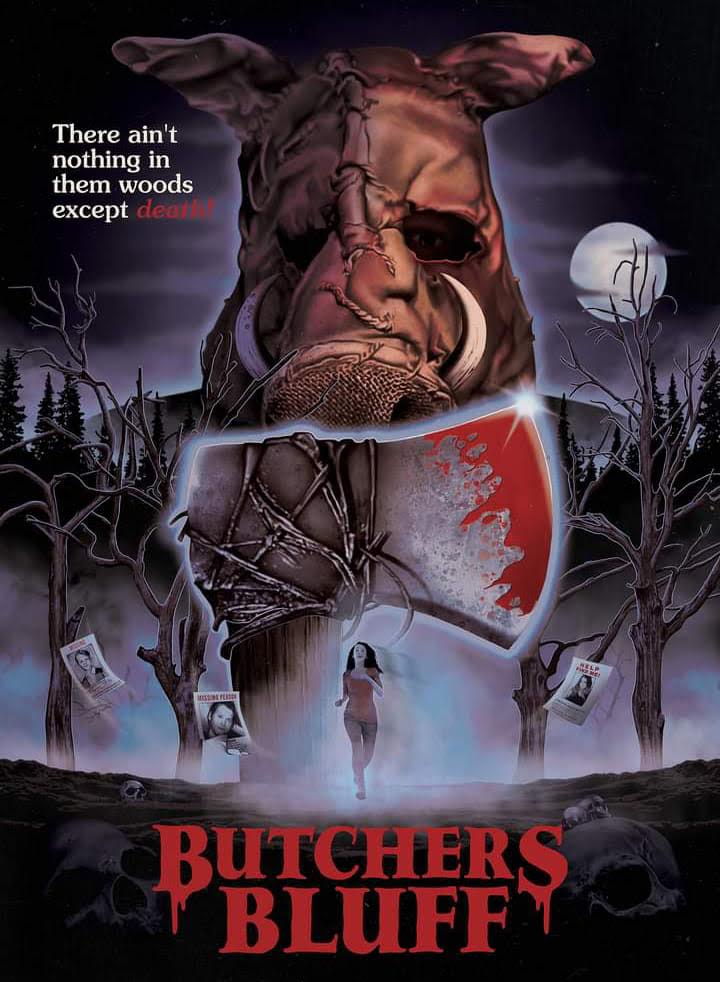

Instone would grow up to make horror films himself. His 2013 feature, Butchers Bluff, wears its TCM heritage proudly on its gore-streaked sleeve. In it, Instone plays a pig mask-wearing killer called the Hogman as he slashes his way through a cast. He made it as an open homage to TCM and a way to reconnect horror to what he considers the golden age.

“No one will ever capture it again,” he says. “The remake was good, but it’s not as great. The original film looks hot. People are sweating in the van. It’s almost documentary-style. As much as our tech has improved and our storytelling can evolve, if it even has, there was a pivotal point, in 1974 we’re never going to match.”

Instone is not the only person weaving bits of blood and bone from TCM into his work. It’s one of the most influential pieces of art of the last century. Pete Vonder Haar has been a movie critic with the Houston Press since 2002, covering a lot of horror in that time. He recently got the new 50th-Anniversary box set of TCM, which comes with a lovely miniature chainsaw his kids enjoyed chasing each other around with.

He sees TCM’s influence everywhere.

“We’ve gone through different waves since then, including the birth of the slasher, the extreme horror of Europe and the body horror of Japan and Korean, and it all starts with Chain Saw,” he says “ It’s the progenitor of everything you’re watching nowadays. The influence might not be evident but it’s in 90 percent of the DNA in what we’re seeing now.

The Bullock Museum agrees with him. The museum recently screened the film with Kim Henkel in appearance. Jessica Hanshaw, Public Programs Manager, felt the movie was in important part of Texas film history and that it should be included in their programming.

Like many people, she sees the figure of Leatherface as one of the great film characters, and unique even in a sub-genre full of masked imitators. Unlike most slashers, Leatherface often appears scared or confused. His first kill in the movie is almost a startled response, more animal than man.

“It’s a combination of the vulnerability and raw brutality in the character,” she says. “Unlike a lot of villains, Leatherface is not purely evil. It’s shaped by his family and their influence. He doesn’t speak, and his erratic violence that goes from silence to explosive. Gunnar Hansen brought so much to the character.”

Instone even jokes that Leatherface is the hero.

“They were intruding into his house,” he says. “This is a home invasion film.”

A half-century after it barreled into theaters, the Teas Chain Saw Massacre still finds new audiences and inspires filmmakers. It's one of the great Texas independent film successes and almost singlehandedly changed the entire horror industry overnight. While hundreds of imitators have come and gone since, Chain Saw endures, as testament to Texas filmmaker can-do attitudes and the lasting effect of an expertly crafted nightmare.

*Though title screen and poster read The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, using the proper spelling of “chainsaw,” the film is legally The Texas Chain Saw Massacre according to its original trademark paperwork. Both titles are correct.

Comments ()