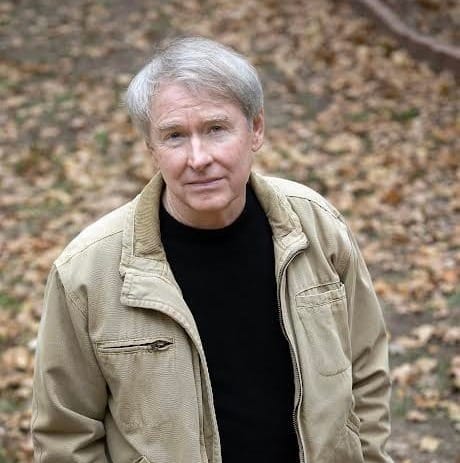

Ben Fountain On His Newest (And Prescient) Novel About Haiti

In his newest novel Devil Makes Three, Ben Fountain creates a gripping tale that takes place in Haiti in the aftermath of the 1991 coup which saw President Jean-Bertrand Aristide deposed by military forces. The story is told from the perspective of three characters trying to navigate their way through the chaos and violence of the new regime. Fountain spoke to Texas Signal about the book, as well as some of his previous works.

Fountain is also the author of the celebrated novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, which was a finalist for the National Book Award and received the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Before writing Devil Makes Three you had been traveling to Haiti for several years, when did you realize this could be a novel?

I made my first trip to Haiti in 1991 and I went two or three times a year for the next 25 years. I felt like things were happening in Haiti in the late eighties and nineties that were so much of a paradigm of how the world works. Who wins and who loses? Who gets the wealth and who gets plundered? Who has the power and who is oppressed? I had an idea for a novel and that [first] trip confirmed this feeling that I had that things were going on in Haiti that I need to try and understand and I continued to go. I wrote that first novel and I finished it in the mid-nineties, it never sold. It didn’t deserve to sell. But I kept going to Haiti and started writing short stories and some reportage about it. By 2012 and 2013 I felt like maybe I’ve got the writing chops now to take another stab. I started writing Devil Makes Three in 2013 and took three and a half years off to write a nonfiction book about the 2016 election. In 2019 I went back to Devil Makes Three and pushed through to the end.

So your first trip was actually right before the coup?

Aristide was elected in December of 1990 on a platform of real popular reform. He took office in February of 1991 and was deposed in a military coup in September of 1991. I was there in May and so I got to be there during this brief window of tremendous hope and optimism and energy. It was an extraordinary moment in time I realize now in retrospect to be there and see that. Of course, the military coup happened a few months later. But I continued to go to Haiti through those years of a really brutal military regime. An international embargo was placed on the country to try and get rid of the military regime but of course it only strengthened their hand. Most of it all it hurt the working people of the country.

The role of the United States throughout these events is something very present in Devil Makes Three.

When bad things happened and certainly the coup was one of those things, one of the first causes many would ascribe is the CIA or the United States. At first, I thought it was kneejerk paranoia, but over the years I began to see there is something to this at various levels. Once I started Devil Makes Three and really started digging into the story of CIA involvement, I began to realize there is a tremendous amount of truth about this folk wisdom of the CIA has [its hands] in everything. There’s not so much that’s come out about Haiti, but there’s quite a bit about the CIA activities in Central and Latin America in the late eighties. I piggybacked a lot of that research into Devil Makes Three because you can see the signs of it in Haiti all over the place. The CIA was doing exactly the same things, but that material hasn’t come out yet. I did a FOIA [Freedom of Information Act] request way back in 2015 to every security agency I could think of, and I’m still waiting for the results nine years later.

A neat aspect of the book is that it’s told from the perspective of three characters. What made you decide to do that?

It was a challenge and a pleasure. The initial reason I set the novel in this particular time period is that the Haitian general who was head of the coup regime was an avid scuba diver and one of his talking points to the press would be well I’m looking for treasure for Haiti, not for myself and if I do find treasure everything will go to the common good for Haiti. This is coming from a man who was skimming who knows how many millions off the international drug trade. I thought it might be interesting to take this aspect of the story, this scuba-diving general and this random American dude who decides to start a dive shop in Haiti.

And that is the first character we meet, the American scuba diver Matthew Amaker.

Yes, [he] finds himself drawn into the inner circle of power of the coup regime thanks to his proximity to the general from scuba diving. That was one part of it. I felt like it was crazy and surreal but also completely true to the absurdity of modern life. I also felt pretty early on the CIA had to be a big part of this story, so that’s where Audrey O’Donnell comes from. She’s a rookie CIA case officer and she’s a true believer in the American mission of free markets, globalism and a certain kind of capitalist friendly democracy. Then there’s Misha Variel. She’s a young Haitian-American woman and she’s getting her PhD from Brown University and she is the sister of Matt’s business partner. And she ends up coming back to Haiti over the Christmas holidays and staying. She’s probably the character who made me work the hardest. I had to learn the most. As I was writing her she seemed to be more and more central to the story.

Were you familiar with scuba diving?

I’ve been once. I had to learn a lot though about scuba diving and the scuba diving business, and then treasure hunting and treasure salvage.

The book really does capture the scary reality of living in a hotbed of violence and cronyism. It was hard not to think of some parallels to the United States now. Could you speak on that?

Let me just start by saying what we’re seeing on the southern border. Waves of desperate human beings. They are refugees from political violence, economic violence.

Many are from Haiti.

Many from Haiti. And all over. Let’s go back to the 1980’s and look at what the Reagan administration was doing in Central and Latin America. The United States devoted a huge amount of energy into [destabilizing] those countries. These things were very much on my mind and very central to Haiti in the period I’m writing about. And then the second part of your question, are we in the United States sliding into that fraying of civil society? I would say absolutely. What you send out to the world abroad, sooner or later it’s going to come back around.

It was hard not to think about our present situations reading the book.

We had an attempted coup. We have had and are having extreme political dysfunction. Extreme political polarization. There’s extremely violent rhetoric. We’ve got environmental disasters unfolding all around us. During the COVID years we had a public health emergency. Here I’m thinking Haiti back then sure looks a lot like the United States now thirty years later.

On a much lighter note, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk has some of the best depictions of sports and football. It’s been on my mind a lot with the hoopla around Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce. Have you felt that way too?

I like that question. This past Super Bowl I was sick. I did go out there in the third quarter, that was about all I could handle. Certainly the world depicted in Billy Lynn, the world of the NFL and pop culture and militarism it’s set in 2004, but that hasn’t calmed down. In fact, it’s only amped up. I haven’t thought about Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift… well I guess she is kinda the head cheerleader.

Very famously she has a song where she isn’t the cheerleader, but I think you’re right. She is one now.

It makes romantic sense that they would get together. It’s all very American.

Comments ()