'Figurative Histories' Explores The Artistic Ascension Of Black Bodies

A new exhibition in Houston brings together four Texas-based Black artists for one goal: to re-contextualize the expression of the Black body in a way that it has rarely been done before

Racism takes hold when the human aspect of a people is reduced or eliminated in the cultural zeitgeist. Most American schoolchildren know that Thomas Jefferson invented the dumbwaiter; almost none know that he did it so that his white guests would not see his Black servants and slaves at parties. The distortion or absence of Black bodies has been a part of America since its founding, as intrinsic as guns, turkeys, and drinking songs.

Figurative Histories, a new exhibition at the Moody Center for the Arts in Houston, brings together four Texas-based Black artists for one goal: to re-contextualize the expression of the Black body in a way that it has rarely been done before. It’s a powerful collection of pieces that runs an emotional gamut from joy to fear to whimsy to inspiration.

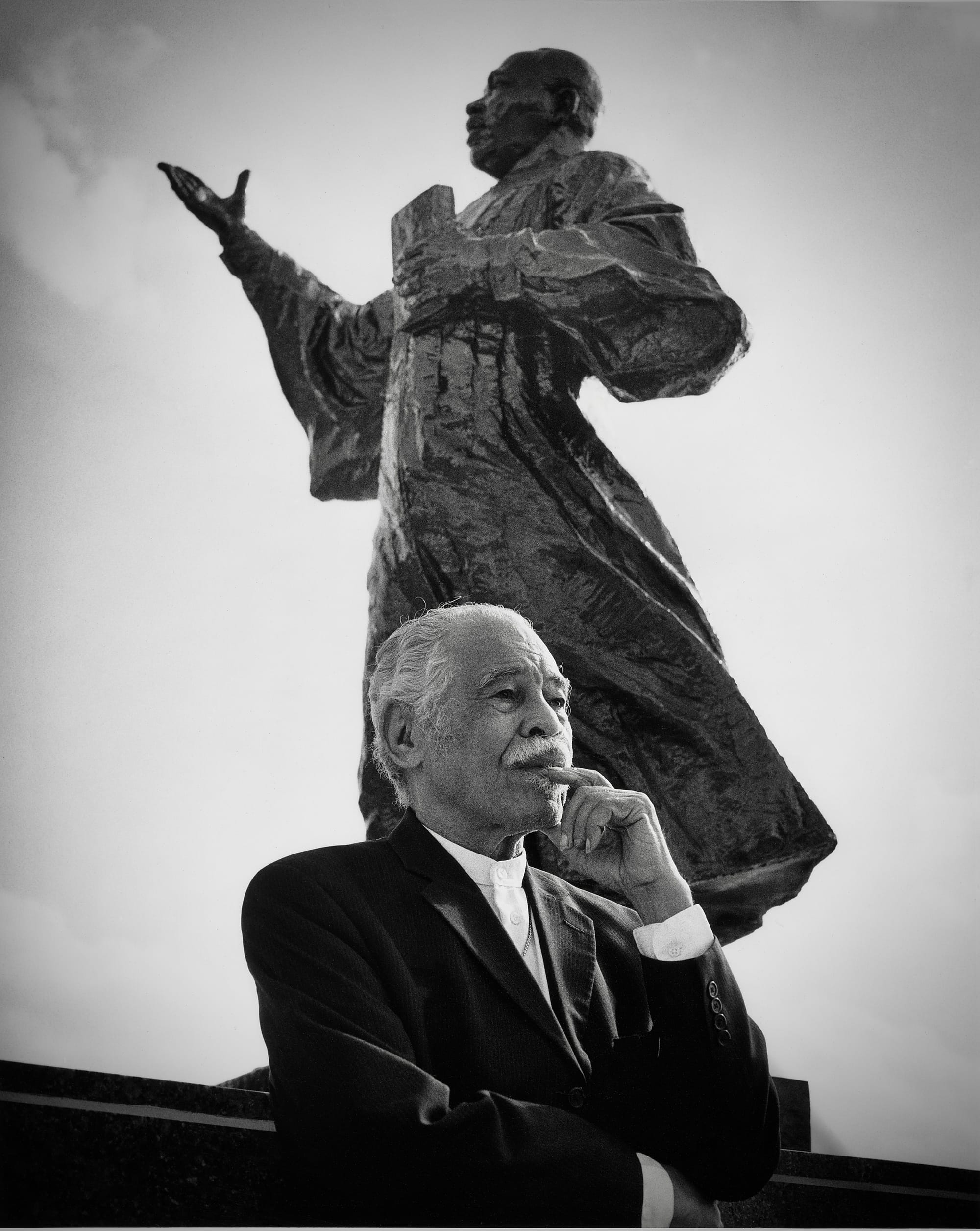

The photography of Earlie Hudnall, Jr. dominates the first part of the show, particularly his portrait of Dr. Thomas Freeman, Hudnall’s mentor and a legendary educator at Texas Southern University, standing under a statue of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The towering piece stands taller than most houses, but Freeman doesn’t stare down a viewer. Instead, his eyes are fixed on an unseen horizon, giving the venerable Houston philosopher and debater the air of a great explorer.

The rest of Hudnall’s collection is smaller and more community centered. Black children play in Fourth Ward yards, flying through the air to land on piled mattresses. People live and work in the closely built neighborhood, and Hudnall’s photos captures the joy so often missing in the artistic collections centered around the Black American experience.

“[I’m interested in] how people live, the university of the human spirit, what we do from day to day, how we struggle, how we weep, and how we rejoice, he said at the opening of the exhibit on May 29. “I was introduced to the city of Houston, and especially the Fourth Ward. This was a community of people who lived close together and sat on the porches in the afternoon to talk. I began to document how people reacted, their movements, their body languages. When I travel, I try to get off the beaten path to understand how people exist, how they love, how they worship.”

Three painters make up the rest of Figurative Histories, grouped together in the side gallery. Letitia Huckaby has several notable pieces in this collection. Her piece, Living Requiem, started out as part of a project by Texas Christian University to give portraits to people important to the university who had been overlooked in the past. Huckaby was tasked with capturing Charlie and Kate Thorpe, a formerly enslaved couple that “did everything but teach.”

The problem was, no pictures of the Thorpes survive. That’s not an insurmountable issue. There are paintings and statutes of Christopher Columbus all over the world, and none of them are based on his actual likeness because he was never painted as a living man.

Huckaby went a much more ingenious route. She photographed descendants of the Thorpes who still lived in the area, then painted them as silhouettes. Placed in ornate wooden frames carved by Huckaby and mounted on a classic Victorian wallpaper, the collection resembles mourning portraits and broaches, a style of art rarely featuring Black subjects. Taken together, the pictures both re-contextualize how we look at Black subjects and also honor the Thorpes through the biological legacy they left behind.

“They are their DNA, after all,” said Huckaby at the opening.

Both Delita Martin and David McGee took more overt approaches to reimagining Black figures in art. Martin, an author and artist from Huffman, presents a collection called The Song Keepers. It shows a series of imaginary women from a magical island called Ebon, where the women protect history through their wisdom. Using a layered approach, her figures seem to emerge straight from the wall, like gods entering a temple.

McGee, meanwhile, is more surreal. His Avenging Angels series resembles Versailles noble portraits, but with a twist. Large, opulent dresses and hairstyles are juxtaposed with food or martial arts weapons, adding strange symbolism to the women seen in the paintings.

“My work is about deconstruction of segregated space,” McGee said at the opening. “I’m interested in how segregated space navigates people. The images around you are influenced by everything from Pam Grier in black exploration films, the feelings of fantasy revenge, Dante, and Don Quixote. This whole idea of reimagining who you are when you come to something that doesn’t involve you. and how that reconstructs your body politic. America has an interesting history of labeling things wrong.”

At every point, Figurative Histories plays with traditional white artistic practices and filters them through an unapologetically Black lens. The result is that reimagining McGee talks about, where the lines of segregation fall and Black humanity is restored by disintegration of arbitrary artistic barriers.

Figurative Histories runs through August 16 at the Moody Center for the Arts in Houston

Comments ()