Houston’s Menil Celebrates 100 Years Of Rauschenberg

Menil Collection in Houston is hosting a collection of fabric pieces in celebration of Robert Rauschenberg's 100th birthday this year

Robert Rauschenberg of Port Arthur is one of the most important artists of the late 20th century. His work was the primary counterargument against Jackson Pollock and abstract expressionism. Where Pollock reveled in his dripping, chaotic creations, Rauschenberg focused on the power of everyday objects to lend weight to art.

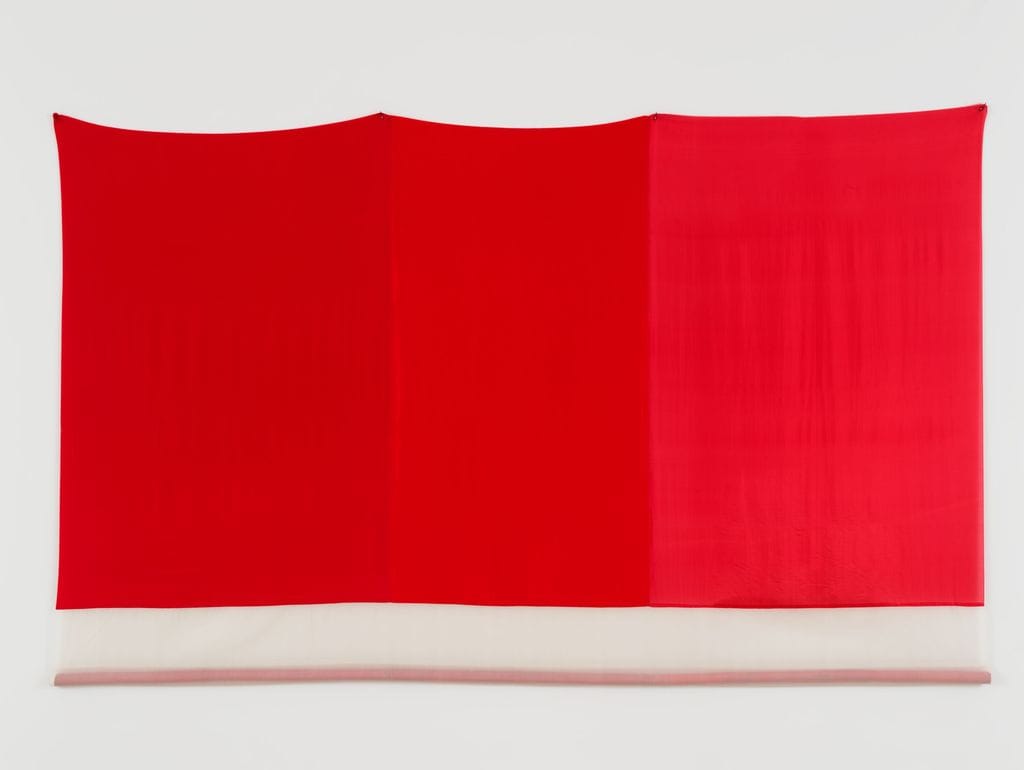

During the 1970’s, Rauschenberg experimented heavily with fabric as a medium. Menil Collection in Houston is hosting a collection of his pieces in celebration of his 100th birthday this year, giving visitors a chance to see this chapter of Rauschenberg’s artistic life.

“This is an exhibition that’s a part of a larger worldwide initiative being sponsored by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in museums around the world, really celebrating his life, his career, and the relevancy of his work now,” said Michelle White, senior curator at the Menil. “John and Dominique de Menil have a long history with Rauschenberg and supported his work early on. This is the fourth major monographic show the Menil has organized in its 40-year history.”

Fabric Works of the 1970s gathers around 30 pieces created by Rauschenberg during his textile period. These include sculptures, canvases, and set dressings. The latter is the most impressive installation in the exhibit, taking up an entire wall in the Menil to transform it into a strange landscape of fabric and machinery.

Rauschenberg collaborated with choreographer Merce Cunningham’s and musician John Cage in 1977 to create essentially a modern art supergroup project called Travelogue. Presented at the Minskoff Theatre in New York, dancers would add and discard everyday items to their costumes as they cavorted. Rauschenberg’s set dressing, which he called “Tantric Geography” was a collection of chairs, bicycle wheels, and multicolored fabric that hung down from the ceiling like sails.

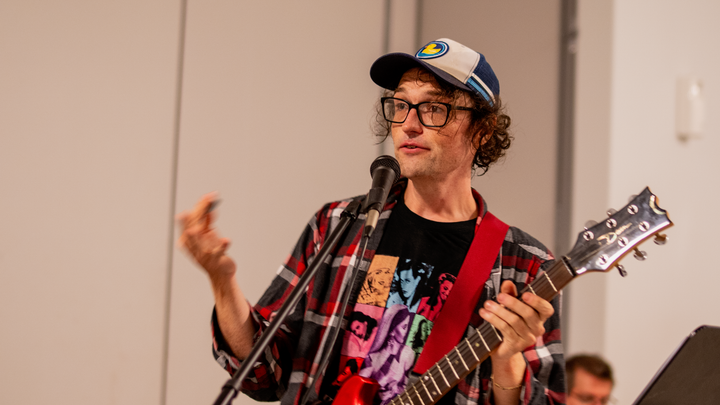

Next to the recreation of “Tantric Geography” is a large television showing a 2023 performance of Travelogue done by the University of North Carolina. Even though the beauty of “Tantric Geography” stands on its own, seeing how it was originally envisioned to be an interactive piece of art in the hands of the dancers lends it majesty.

It’s a prime example of the power of fabric art and why Rauschenberg was so enamored with it. Fabric is not static. The image of it changes with wear, wind, and even the amount of light that flows through it. It’s a mercurial medium directly tied to life and motion.

“For Rauschenberg, what I was interested in was to dig into why he was thinking about fabric as such an interesting, almost transgressive material,” said White. “In the ‘70s, he’s middle-aged, but what’s so cool in the ‘70s is that he’s still experimenting and pushing materials. For him, it really is this material that represents the everyday. What could be more familiar, more intimate for anyone looking at a work of art than a piece of cloth? I think Rauschenberg really recognized the potency of cloth in terms of its deep association to the body, its association to the familiar, to life."

Throughout the 1970s, Rauschenberg continued to try new things with fabric. One of his most famous pieces on display in the Menil is Sant’ Agnese (Venetian), constructed in 1973. It’s a length of mosquito netting stretched across two wooden chairs, held in place with shoelaces. Hidden in the fabric are two corked glass jugs.

At first glance, Sant’ Agnese looks like an innocuous pile of junk, about as artistic as a back alley after a busy day. However, the choice of netting plays at Rauschenberg’s love of everyday contrasts. It’s simultaneously dimorphous and opaque, letting in light but also providing a sense of privacy similar to a blanket fort. There’s no denying that it’s architecture, but we’re so unused to seeing such materials constructed as carefully as a cathedral that it is as transgressive as White says.

Every piece in the exhibition is like that. Rauschenberg famously painted directly onto his own quilts and blankets, turning pieces of mundane life into expressive art that changed as it was wrapped around the body or discarded. Is there any artistic difference, really, between painting a flag fluttering in the breeze and actually having a flag fluttering in the breeze? Rauschenberg says no, and he backs it up well in the Menil Exhibition.

Fabric Works of the 1970s is on display at the Menil through March 1, 2026.

Comments ()